Locks play a big role in safeguarding our homes, businesses, and personal belongings. But what exactly goes into the making of these silent sentinels that stand guard day and night? Join us as we embark on an enlightening journey through the intricate world of locks, exploring their components, how they work, and why they continue to be the cornerstone of modern security. Prepare to unlock the mysteries as we dissect the anatomy of a lock.

Understanding Lock Components

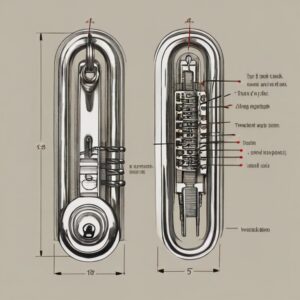

Locks may vary in sophistication and design, but the basic anatomy of a traditional lock remains consistent.

The Lock Body/Cylinder

Central to a traditional lock is the lock body or cylinder, which houses the core elements that drive the functionality of a lock. The cylinder is the area that you insert a key into. When the correct key is inserted into the cylinder, it triggers the alignment of internal pins, allowing the lock to open.

The Pins

Within the cylinder, you find an array of pins, typically in pairs: key pins and driver pins. These pins are the bits that respond to the unique shape of a key. Key pins touch the key directly, and their heights match the grooves and notches on the key. Driver pins sit on top of the key pins and push against a spring. When a key is not inside the cylinder, the springs force the driver pins down, which prevents the lock from turning.

The Springs

Springs in a lock mechanism provide necessary resistance. Each pin pair has a corresponding spring which ensures that the pins can return to their original position after being pushed by the key. These small metal coils are stalwarts when it comes to returning the lock to a secure state post-use.

The Shear Line

An undeniably critical aspect of a lock’s anatomy is the shear line. It is the physical line that aligns when the correct key lifts the key pins to the correct height, causing the driver pins to meet the edge of the cylinder, providing a clear path for the lock to turn. When the pins are in the right place, a harmonious line is created – the shear line.

The Plug

Often confused with the cylinder, the plug is actually the component within the cylinder that turns with the key. The plug contains the keyway, which is essentially the outline that keys must match to fit. When the correct key is inserted and the pins align at the shear line, the plug can rotate, initiating the lock’s opening mechanism.

Pick Resistance and Complexity

Lock security is important for protection against unauthorized access, and as a response to lock-picking threats, manufacturers employ advanced techniques by integrating security pins such as spool, mushroom, and serrated pins into their lock designs. These pins are cleverly engineered with unusual shapes to interrupt the typical process that lock picks rely on. When an attempt is made to pick the lock, these security pins bind in a way that differs from standard pins, often at the sheer line—the critical juncture where the inner cylinder of the lock turns independently from the outer casing. This feature creates an additional set of challenges for a lock picker because they introduce an element of unpredictability and resistance. The pins tend to get caught or give false feedback, which can lead lock pickers into thinking they have successfully set a pin when, in fact, they have not. With security pins in place, even if a lock picker applies the correct amount of torsion and successfully lifts the pins to the sheer line, the unique shape of these pins will disrupt the process, thus preventing the cylinder from turning and the lock from opening easily. This increases the level of skill and time required to pick the lock, providing an effective deterrent and significantly enhancing the lock’s overall security profile.

From Traditional to Electronic Locks

The evolution of lock technology has transitioned from mechanical intricacies to sophisticated electronic systems. These contemporary electronic locks have redefined security measures by incorporating advanced features that provide user-friendly access while maintaining rigorous control over who can enter. Keypads eliminate the need for physical keys, allowing entry through a numerical code that can be easily changed to maintain security when necessary. Card-reader systems leverage technology similar to what is used in credit card transactions, by issuing access cards that communicate with the lock through magnetic stripes or RFID technology, access management becomes both flexible and trackable.

Perhaps the most personal form of these innovations is found in biometric systems. These systems use unique physical characteristics such as fingerprints, iris patterns, or facial recognition to grant access, ensuring that only programmed individuals can unlock the door. The use of biometrics adds a layer of security that is difficult to replicate or transfer, hence increasing the resilience against unauthorized entry. Even so, the goal of any lock remains constant: to allow authorized individuals a seamless entry while preventing access to all others. Electronic locks often combine several of these features to provide multiple authentication methods, adding an extra layer of security commonly referred to as multi-factor authentication. With these electronic locking systems, security protocols become more robust, customizable, and suited to a wide range of applications, from personal residences to high-security areas in commercial settings.